Implicit bias in special education has become a growing focus for educators and policymakers as schools grapple with persistent disparities in how students are identified, disciplined, and placed into disability programs. Research suggests that unconscious assumptions—rather than deliberate discrimination—continue to influence critical decisions, shaping long-term academic and life outcomes for millions of children.

Table of Contents

A System Built to Support—and Sort

Special education in the United States was designed to ensure equal access to education for students with disabilities. The modern system emerged from the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, later renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which guaranteed students a “free appropriate public education.”

Yet from its earliest years, federal data showed uneven patterns. Students from marginalized racial, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds were disproportionately placed into certain disability categories, particularly those relying on subjective judgment rather than medical diagnosis.

Those disparities have proven remarkably durable. Nearly five decades later, implicit bias in special education remains a central explanation offered by researchers seeking to understand why reform efforts have not fully closed the gap.

What Implicit Bias Means in Educational Practice

Implicit bias refers to unconscious attitudes or stereotypes that affect understanding, actions, and decisions. Unlike explicit bias, it operates without awareness and often contradicts stated beliefs about fairness and equality.

In schools, implicit bias may shape how educators interpret student behavior, academic struggles, or communication styles. These interpretations matter most during moments of discretion—when teachers decide whether to refer a student for evaluation, how to describe behaviors in reports, or how urgently to pursue interventions.

“Bias shows up where there is ambiguity,” said Dr. Russell Skiba, a professor emeritus at Indiana University and a leading researcher on discipline and equity. “Special education decisions often involve gray areas, which makes them especially vulnerable.”

Disproportionality: A Persistent Statistical Pattern

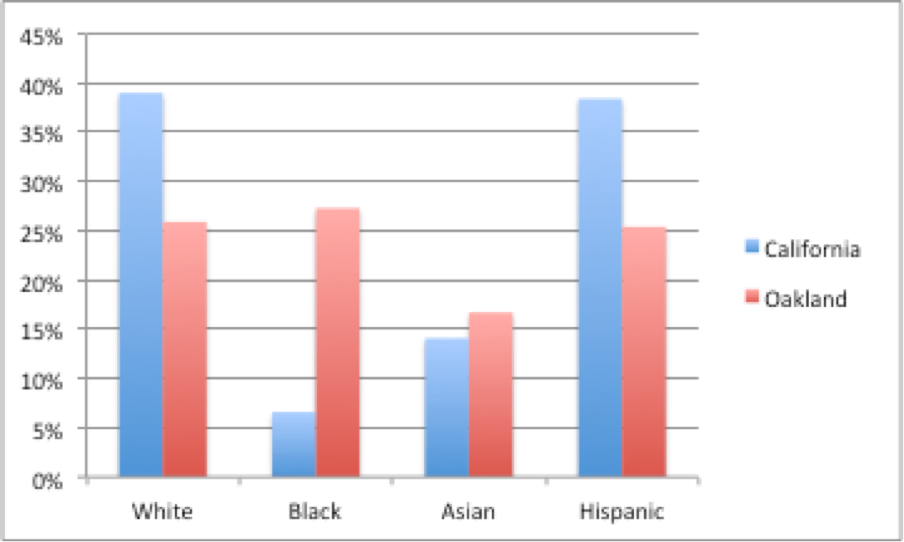

Federal law requires states to monitor disproportionality in special education identification. The data consistently reveal stark differences across racial and ethnic groups.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, Black students are significantly more likely than white students to be identified with emotional disturbance or intellectual disability—categories that often lead to more restrictive educational settings. White students, by contrast, are more frequently identified with learning disabilities, which typically allow greater inclusion in general education classrooms.

Researchers emphasize that these patterns are not explained by higher rates of disability. Instead, they reflect how academic difficulty and behavior are interpreted through cultural and institutional lenses.

Behavior, Discipline, and the Path to Identification

Behavior plays a critical role in the special education pipeline. Multiple peer-reviewed studies have found that students of color are more likely to be disciplined for subjective infractions such as defiance or disruption.

Disciplinary referrals often trigger evaluations for emotional or behavioral disabilities. Once identified, students may be removed from general education classrooms, reinforcing academic gaps and social stigma.

“Discipline is not a side issue,” said Daniel Losen, director of the Center for Racial Justice Remedies at UCLA. “It is one of the main entry points into special education, especially for behavioral categories.”

Teacher Expectations and Academic Opportunity

Implicit bias also shapes expectations—often in subtle ways. Research shows that teachers’ beliefs about student potential influence instructional choices, such as whether to offer advanced material, provide feedback, or encourage persistence.

Lower expectations can become self-fulfilling. Students placed in restrictive settings receive less exposure to grade-level content, making it harder to demonstrate progress that could justify exiting special education.

Educators interviewed across multiple districts emphasized that most teachers enter the profession with strong equity commitments. However, systemic pressures—large class sizes, limited time, and high-stakes accountability—can amplify reliance on mental shortcuts.

The Family Perspective

For families, special education decisions can feel opaque and intimidating. Parents often report confusion about evaluation criteria and limited ability to challenge professional judgments.

Advocacy groups note that families with fewer resources or limited English proficiency face additional barriers. Navigating assessments, meetings, and legal rights requires time and expertise many households lack.

“Parents sense when decisions are being made about their child rather than with them,” said a policy analyst at a national disability rights organization. “That erodes trust and worsens outcomes.”

Long-Term Consequences Beyond School

The impact of special education placement extends well beyond K–12 education. Longitudinal studies show that students placed in more restrictive settings are less likely to graduate, enroll in college, or secure stable employment.

A report from the Government Accountability Office found that students with emotional disturbance had among the lowest graduation rates of any disability category. Advocates argue that early misidentification can set students on paths that are difficult to reverse.

These outcomes raise broader economic and social concerns, particularly as policymakers focus on workforce participation and social mobility.

Training, Data, and Institutional Safeguards

In response, districts nationwide have expanded educator bias training and revised evaluation procedures. Many now require:

- Multiple data sources before referral

- Culturally responsive assessments

- Multidisciplinary evaluation teams

- Periodic review of placement decisions

The National Association of School Psychologists recommends explicit bias checks during eligibility determinations, asking teams to consider whether cultural, linguistic, or environmental factors better explain observed difficulties.

Still, evidence suggests that one-time trainings have limited impact. Researchers increasingly emphasize systemic redesign rather than individual awareness alone.

Technology and the Promise—and Risk—of Objectivity

Some districts are turning to data analytics and artificial intelligence tools to flag disproportionality or standardize referrals. Proponents argue that algorithms can reduce subjective judgment.

Critics warn, however, that technology can replicate existing biases if trained on biased data. Without transparency and oversight, automated systems may reinforce the very disparities they aim to eliminate.

“Technology is not neutral,” said a senior fellow at a national education think tank. “It reflects the values embedded in its design.”

How Other Countries Approach the Issue

International comparisons offer useful context. Countries such as Finland and Canada emphasize early intervention and inclusive classroom supports, reducing reliance on categorical disability labels.

In many European systems, special education services are delivered without formal classification, limiting the stigma associated with disability categories. Researchers caution that cultural differences make direct comparison difficult, but note that less reliance on subjective labeling correlates with lower disproportionality.

Policy Debates and Federal Oversight

Under IDEA, states with significant disproportionality must redirect funds toward early intervention and corrective action. Civil rights groups argue that enforcement remains uneven.

Education leaders counter that overly rigid rules could delay support for students who genuinely need services. The debate reflects a broader tension between equity safeguards and operational flexibility.

In recent guidance, the U.S. Department of Education emphasized that disproportionality should be addressed through “systemic solutions rather than punitive measures.”

What Comes Next

Experts broadly agree that reducing implicit bias in special education will require sustained effort rather than quick fixes. Greater transparency, stronger data systems, family engagement, and ongoing professional development are widely cited as essential.

“Bias thrives in silence and routine,” Skiba said. “The more schools question their assumptions, the fairer outcomes tend to be.”

FAQs About Understanding Implicit Bias in Special Education

What is implicit bias in special education?

It refers to unconscious assumptions that influence how students are evaluated, identified, and placed into special education programs.

Is disproportionality evidence of discrimination?

Not necessarily intentional discrimination, but it signals systemic issues that require corrective action.

Can implicit bias be eliminated?

Research suggests it can be reduced, but not eliminated, through sustained institutional safeguards.

Does special education harm students?

When appropriately applied, it provides essential support. When misapplied, it can limit opportunity and long-term outcomes.